It is not uncommon for folks to get confused when they encounter differences in vocabulary between, say, the Didache and Apostolic Constitutions and the writings of St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Pope St. John Paul lI. There is, of course, every possibility that one sentence or another could be mistaken–but, really, when you do check up on them, there is a remarkable consistency.

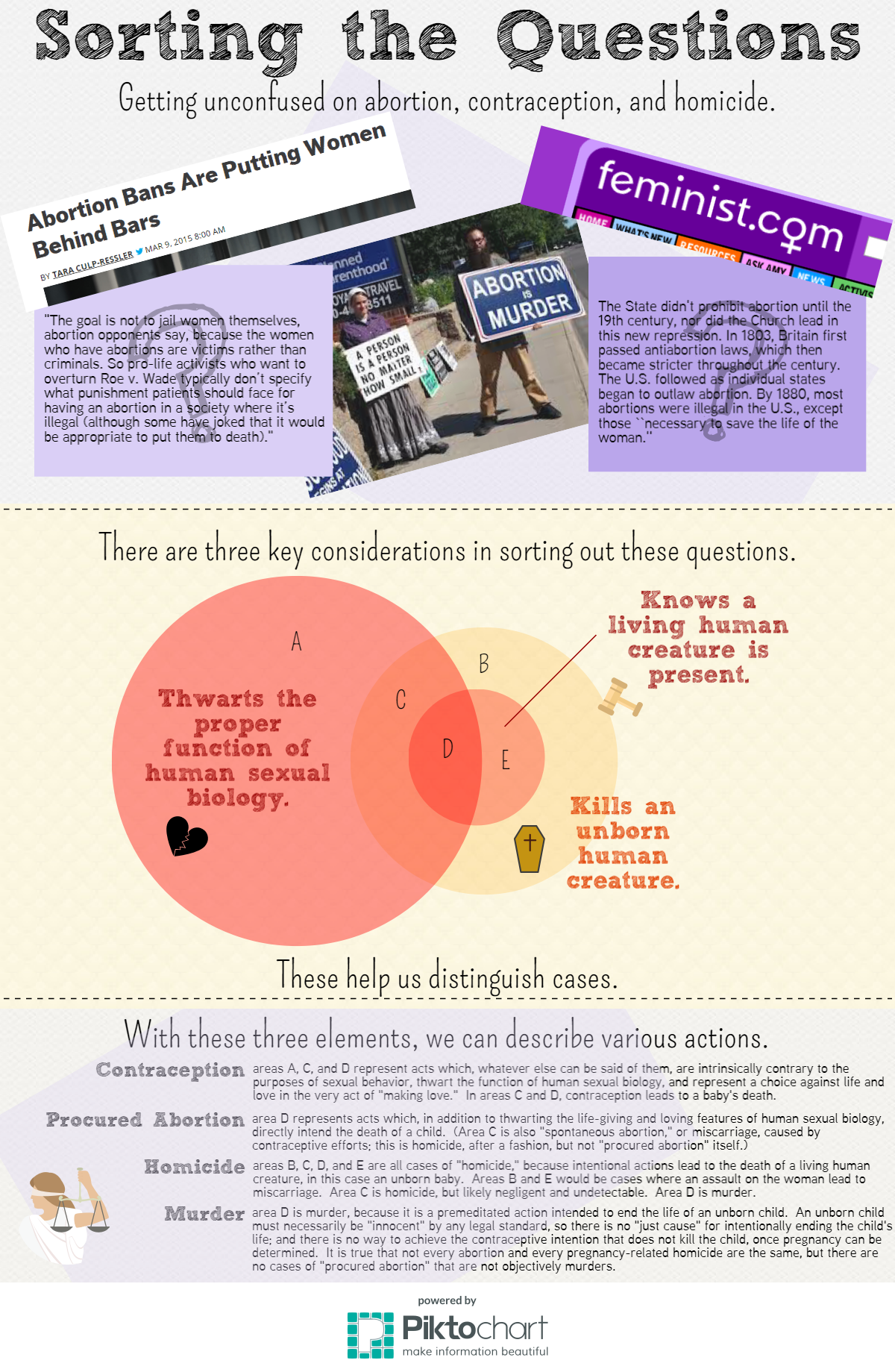

The confusion lies in that any one of these, or hundreds of others, may well be discussing a question such as “Is thus-and-such a case a matter of contraception or of homicide” with regard to the objective and subjective guilt–both relevant in moral theology, and not always tidily distinguished–that was relevant to some contemporary discussion that may not be obvious to a casual reader.

When you do read the whole discourse, however, it becomes clear that at issue here is how the ascertainable presence of a baby affects the judgment of all those involved, and thus what intentions it is possible for them to have formed (objective guilt involved in the act performed) and what degrees of culpability they might have (subjective guilt modified by the agent’s freedom, knowledge of fact, and knowledge of law). If a man negligently causes injury to a woman, and death to a child he does not know she has, is that different than if he knows she has the child? If a woman attempts to prevent conception, and causes an abortion, is she guilty of contraception or homicide? Is abortion reducible, in every case, to either contraception or homicide, or is there some distinction (objective or subjective) between them? These are the questions the tradition dealt with, long before the advent of modern medicine that could ascertain the presence of a baby very nearly as soon as it is conceived.

So, in an effort to clarify the principle here, I’ve drawn a picture: